Key Takeaways

Unlike with baseball hits, fixed income excess returns resemble a normal distribution, but as volatility increases, there’s a greater chance of underperforming.

Bonds should provide stability, not volatility. An overly aggressive approach at the plate can lead to strikeouts, and an unpredictable return profile.

At Voya, rather than trying to tear the cover off the ball, we believe consistently good results that come from a high batting average lead to better investor outcomes.

Batting average may be outdated in baseball, but with bond investing, it can drive performance that’s consistently good rather than occasionally great.

Ever wonder why you rarely see batting averages above .300 these days? While greats of the past—players like Ty Cobb, Ted Williams and Tony Gwynn—consistently hit over .300, good luck finding recent players on the list of top lifetime batting averages. Some say the falloff stems from a shift away from focusing on batting average and playing small-ball toward slugging percentage and extra-base hits.

It often makes sense for today’s ballplayers to swing for the fences rather than hit into the gap or drop down a bunt. Big swings can yield an immediate and impactful result: the “occasionally great” performance, which hopefully makes up for the higher likelihood of a strikeout. Situational hitting and quality at-bats require persistence and patience—the “consistently good” feat.

We too ponder the tradeoffs of being too aggressive when building fixed income portfolios. But there’s a key difference between bond managers and ballplayers—a swing and miss in investing has much bigger consequences. Not only can you squander the opportunity for positive performance, but you can also lose what was previously gained.

The consequence of a strikeout is greater in investing

What makes a successful at-bat? Other than driving home a run, baseball statisticians looks at on-base percentage, batting average (BA) and more recent sabermetrics such as slugging percentage (SLG). Whereas BA treats all hits equally, SLG weighs extra-base hits higher than singles. Modern baseball analytics have shown that going 1-for-4 with a home run adds more team value than going 3-for-4 with three singles.

In a game where two-thirds of at-bats result in an out, a critical factor to batting strategy is that teams can’t lose the runs they’ve already put on the scoreboard. That means batters are encouraged to reap the rewards for slugging a home run, despite the low odds, giving rise to asymmetrical outcomes. In other words, there is no left-tail risk.

If only investing were similarly a matter of degrees of upside. But alas, fund managers must factor in the risk of loss. Whereas at-bats have no downside, bond fund returns are distributed to both the upside and downside. We examined 15 years of quarterly return data in Morningstar’s Intermediate Core Plus bond category; managers with plate discipline—which we define as excess returns within one standard deviation of the mean—had a 63% chance of outperforming their benchmark. But when they tried for the moonshot—reaching for excess returns beyond one standard deviation—the chance of underperforming increased exponentially as volatility increased (the so-called left-tail risk).1 This negative skewedness means the potential loss with a swing and miss is often greater than the possible gain.

The Mendoza Line for adequate management

No investor wants to hand over their money to an inadequate portfolio manager, just like no club wants to have unskilled hitters in its lineup. But how do you know what “adequate” looks like?

Baseball’s line of adequacy—infamously known as the Mendoza Line—falls at a .200 batting average.

We believe the threshold of investing adequacy needs to be significantly higher—let’s say better than average. To establish that mark, our previously cited data show that approximately 60% of quarterly observations outperformed the benchmark over the past 15 years. So, we set the line of adequacy for core plus bond fund managers at a 60% batting average.

Is your manager above the Mendoza Line?

Hitting leadoff, not cleanup, offers better results in investing

As the baseball playoffs quickly approach, the season’s top five home-run hitters have collectively hit 208 home runs, accounting for nearly 30% of their hits.2 However, they have also struck out 648 times, roughly one in every four trips to the plate.

For investors, strikeouts show up as underperformance as swing for the fences portfolio managers can (and do) strikeout. These strikeouts often lead to a volatile excess return profile—the opposite of what investors want from their bond allocation.

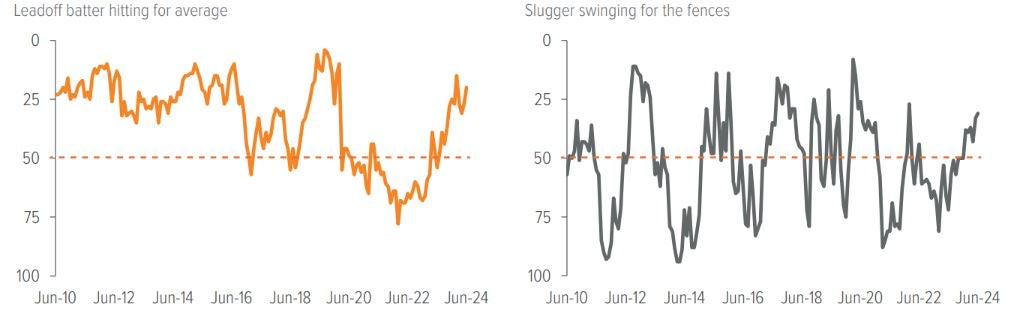

To see these statistics play out in investment performance, take a look at rolling excess return rankings. A fund that hits for average is going to spend more time above median, as opposed to a proverbial slugger whose excess return rankings will swing wildly above and below the midline (resulting from a higher tendency to hit home runs and strike out).

In our hypothetical example, the leadoff batter that hits for average spends nearly 80% of the time above median while the home run slugger spends more time below median (Exhibit 1).

Hitting a home run in bond markets is hard, whereas striking out is a more frequent occurrence, and could produce actual dollar losses, which may impact an individual’s wealth plan or potentially delay retirement or other goals.

At Voya Investment Management, we think more like a leadoff hitter. We aim to get on base every time— a mindset of consistently good—so we can deliver strong long-term returns and less volatile short-term performance. Because for bond investors, especially those near or in retirement, a fund that tries to bring the crowd to their feet by smashing the ball out of the park each time they step up to the plate simply adds unnecessary risk. Who do you want batting in your lineup?

Source: Voya IM. For illustrative purposes only.

At Voya Investment Management, we think more like a leadoff hitter. We aim to get on base every time—a mindset of “consistently good”—so that we can deliver strong long-term returns and less volatile short-term performance. Because for bond investors, especially those near or in retirement, a fund that tries to smash the ball out of the park each time it steps up to the plate simply adds unnecessary risk. Who do you want batting in your lineup?

A note about risk The principal risks are generally those attributable to bond investing. All investments in bonds are subject to market risks as well as issuer, credit, prepayment, extension, and other risks. The value of an investment is not guaranteed and will fluctuate. Market risk is the risk that securities may decline in value due to factors affecting the securities markets or particular industries. Bonds have fixed principal and return if held to maturity but may fluctuate in the interim. Generally, when interest rates rise, bond prices fall. Bonds with longer maturities tend to be more sensitive to changes in interest rates. Issuer risk is the risk that the value of a security may decline for reasons specific to the issuer, such as changes in its financial condition. |