Myths and misapprehensions about private credit often seem to get more airtime than facts. Here’s a look beyond the headlines at what the market’s really like.

I’m on the road a good 150 days a year meeting with colleagues, investment partners, borrowers and potential clients about private credit, and I hear a lot of uncertainty about where it belongs in a portfolio. That’s natural—private credit is a wildly diverse asset class that gets talked about like it’s all cov-lite sub- $100 million direct loans, when the majority of issuance is actually covenant-heavy $370+ million investment grade private placements (which, by the way, have historically been less risky than comparable investment grade corporate bonds—see Exhibit 2).

It doesn’t end there. Just in the past week, I’ve heard that private credit is a) disintermediating banking, b) a way of avoiding regulation, and c) illiquid. [Sigh.] Let’s shoot down a few myths about this industry.

Myth #1: Private credit is another name for middle market loans

When outsiders talk about how risky private credit is, they’re generally talking about middle market direct lending. In truth, that’s just one of three main ways corporations borrow medium- and long-term money in the private market (Exhibit 1). What’s more, the middle market is both the smallest segment of the private credit universe (in terms of total dollar issuance) and the most diverse.

As of 09/25/24. Source: Debtwire, Fitch, Morningstar, CDLI, BoA, Voya IM estimates. *The middle market is extremely heterogenous but can be broadly broken out into lower middle market (tranche sizes less than $100mn), core middle market ($100-500mn) and upper middle market (over $500mn). The upper middle market overlaps with the BSL market.

By contrast, investment grade private credit (PCIG) is a large, stable market dominated by insurance companies and pension funds. PCIG is a fixed income product, deployed as a substitute for IG corporate bonds by nearly every life insurer and half of pension funds to enhance diversification and yield. PCIG lending generally falls into three categories: corporate, infrastructure and asset-based finance.

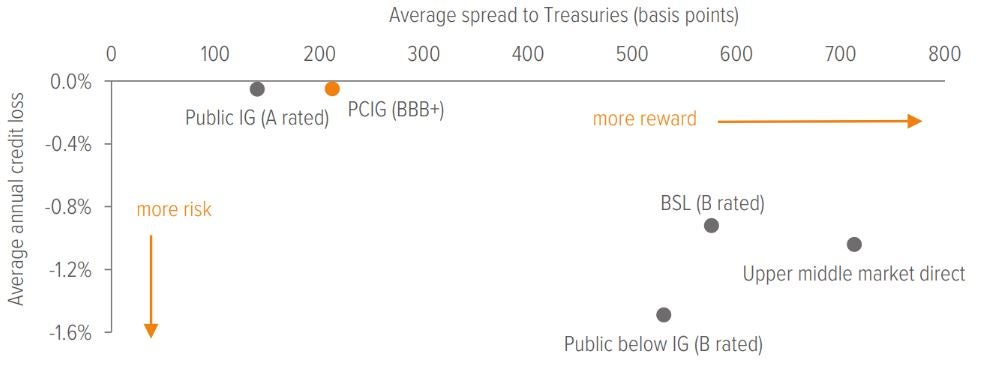

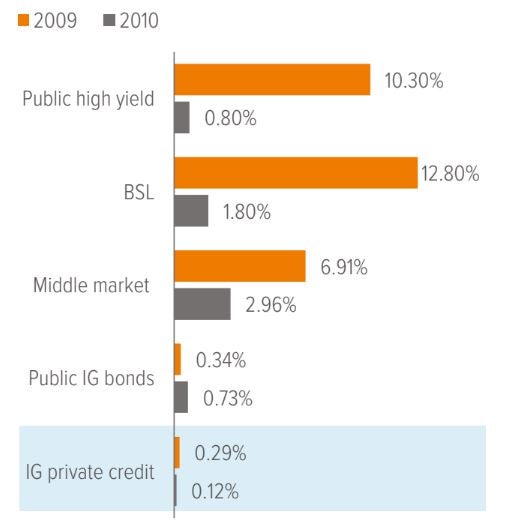

Of all the ways to loan long-term money to corporate borrowers, PCIG has historically been one of the least risky, with loss ratings for BBB+ private placements equivalent to higher-rated (A) public bonds (Exhibit 2). So by adding PCIG to fixed income portfolios, you’re likely reducing risk while picking up about 100 basis points of yield over equivalent public corporate bonds (including the spread plus any back-end prepayment or amendment income).

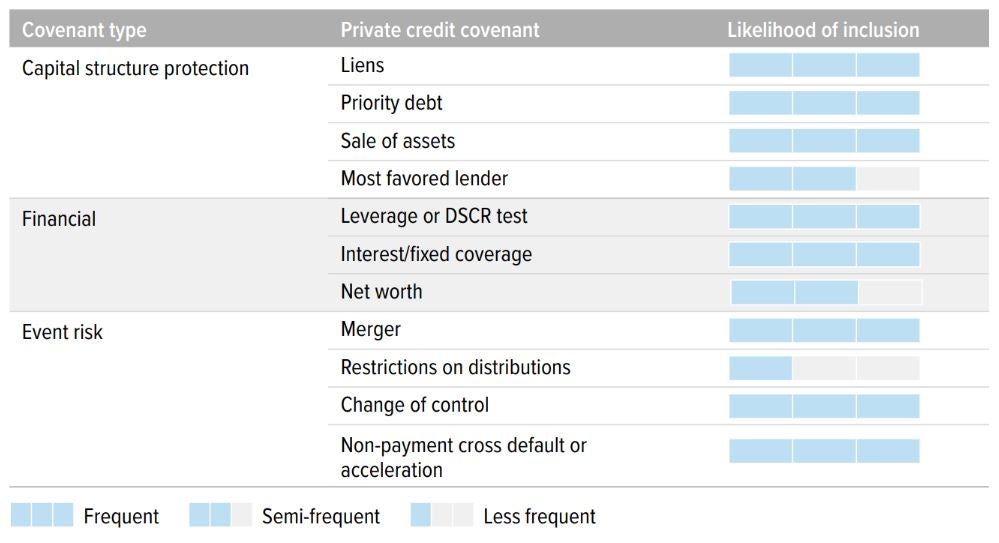

A big reason why PCIG has been good at mitigating loss is its heavy emphasis on covenants. Covenants are safeguards above and beyond securing debt on an asset.1 They’re meant to alert investors quickly in the event of an adverse turn in the company, but they also frequently provide opportunities for non-coupon income, such as amendment fees, waiver fees, rate bumps and make-whole premiums (Exhibit 3).

Takeaways

- The least well-known part of the private credit market is also its largest part: Investment grade private credit (PCIG), which is historically less risky than IG corporate bonds—and yes, it’s liquid.

- The broader PCIG market’s growth spurts are largely due to regulation limiting bank capital available for corporate lending.

- Borrowers choose PCIG to keep their financials private, to have a more tailored debt solution than banks or the bond market can provide, and because the private market remains open in times of stress.

As of 09/25/24. Source: Standard & Poor’s, Morningstar, BoA, CDLI, Society of Actuaries, Voya IM estimates. Average annual credit loss and average spread over risk free are measured over the 18-year period 01/01/05-12/31/22; spreads are tighter across the board at present.

We’ve always believed you have to structure covenants the right way so you can get to the table early enough, while there’s still a businesss to salvage. We hold to this approach across our private credit teams, whether it’s PCIG, Enhanced Middle Market Credit (EMMC), or Renewable Energy Infrastructure Debt (REID).

Don’t believe me. Believe the PhDs:

“For investment grade firms, tightly set covenants allow creditors to demand full repayment while the firm is still solvent. This ensures that creditors sustain no loss regardless of the underlying default probability, mitigating their concerns about the firm’s financial health and alleviating adverse selection in lending.”2

Myth #2: Private credit is illiquid

When people ask, “Is private credit liquid?”, what they’re really asking is, “If I need to raise cash in a hurry, can I sell this quickly at market value?”

The answer is usually yes. There is plenty of sell-side liquidity, because demand for PCIG outstrips supply.

The typical PCIG deal is about $370 million across 12 participants.3 These investors almost never get the full allocation they want, and so they follow the credit actively and look to buy more if it becomes available.

There is a fairly steady volume of secondary PCIG trading each year, totaling about $4 billion among a handful of specialist firms—versus around $70-80 billion of annual new issuance.4

The reason secondary market volumes aren’t larger is because the pension funds and insurance companies (who are the main investors in PCIG) don’t trade their private credit portfolios the way they might a public corporate bond portfolio. Most investors are happy to sit on their holdings for as long as possible, quietly collecting a yield premium over comparably rated corporates and outperforming the benchmark. The big drivers of secondary PCIG volume tend to be M&A activity—firms selling out or transferring entire portfolios post acquisition—or accounting and tax trades.

At Voya, our superpower has always been our great relationships across intermediary agents and major originating insurers/ private equity sponsors (and our lack of direct competition with either group).

For clients, this means we can provide better allocations across more deals from more sources than most of our peers. For clients just starting to build a PCIG allocation, we recommend agented deals, which allow for a faster sale if they ever need to raise cash. With agented deals averaging 12 participants, it’s relatively easy to sell to someone else in the syndicate—they already know the deal and have said yes to it.

The fewer people in a syndicate, the more time it takes to find a buyer when you need to sell. Plus, there’s no real yield difference between direct PCIG deals and agented deals.

Myth #3: Private credit is disintermediating banks

There is no question that banks have been disintermediated from the private corporate lending space in the past 15 years. But here’s the thing: Private credit isn’t to blame. We’re not stealing business from banks by undercutting their pricing (if anything, we charge a premium to the traditional bank market, and our loans come with many more restrictions). We haven’t built a better mousetrap, either. We’re not winning business away from banks because we lend more efficiently or we make the process easier for borrowers.

So what is disintermediating banks from the investment grade corporate lending market?

It’s regulation.

Banks have less capital available to make big loans to corporations due to onerous regulation passed in response to the global financial crisis. This doesn’t mean that banks can’t make loans, or even that they’re prevented from making risky loans. (See: Signature Bank, Silicon Valley Bank, everyone who loaned money to Elon Musk to buy Twitter.) They are just not able to make as many large corporate loans as they could before the global financial crisis.

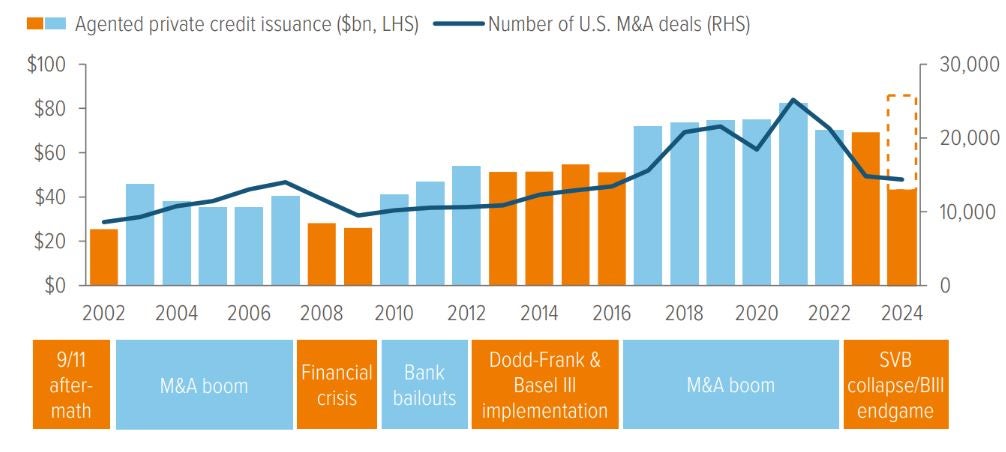

At the same time, there’s more demand for debt capital from corporations than ever before. A good proxy is the amount of M&A activity per year: The more transactions, the more debt capital is generally needed. PCIG issuance grows broadly in line with the M&A market, except in times of banking retrenchment or regulation, when it outpaces the market (Exhibit 4).

This is the real secret behind the rise of PCIG. It’s growing in response to banking disintermediation; it’s an effect, not a cause.

Banks are also increasingly reaching out to private credit lenders on the investment grade side, which has never happened before. There’s always been a fair bit of overlap between the syndicated loan market and the upper middle market, with lead banks coming to our EMMC business for participation lenders for floating-rate loans and vice versa.

As the dust settled on the Silicon Valley Bank fiasco, however, bank desks started asking us if we’d be interested in their investment grade business, too—because they couldn’t fill out their latest BBB bank loan syndicate with banks. In other words, they’re asking us to disintermediate them.

As of 09/30/24. Source: BoA, IMAA, Voya IM. 2024’s figure of $85.8bn (dotted line) is annualized from the 1H24 actual of $42.9bn.

Myth #4: Private credit is risky and under-regulated

First, straight up: I’d be surprised if there’s not an attempt at more regulation of certain segments of the private credit market over the next few years. Non-bank private credit is now about the same size as the BSL market, and when a financial market gets large, people start worrying about systemic risk and wanting more knowledge and oversight. That’s fine.

However, regulation is unlikely to have the restrictive effect on PCIG issuance that post global financial crisis regulation had on corporate bank lending, for a few reasons: Pensions and insurance companies are already highly regulated anyway. Their balance sheets have much less leverage than banks’. And there’s already a high degree of transparency in the PCIG market, because all these issuances are public Reg D filings.

Every PCIG issue has a CUSIP, and insurance companies have to report those CUSIPs in their statutory filings. That’s how we know, for example, that the top 100 life insurers have a weighted-average PCIG allocation of 13.7% as of year-end 2023, up from 10.2% in 2017.5

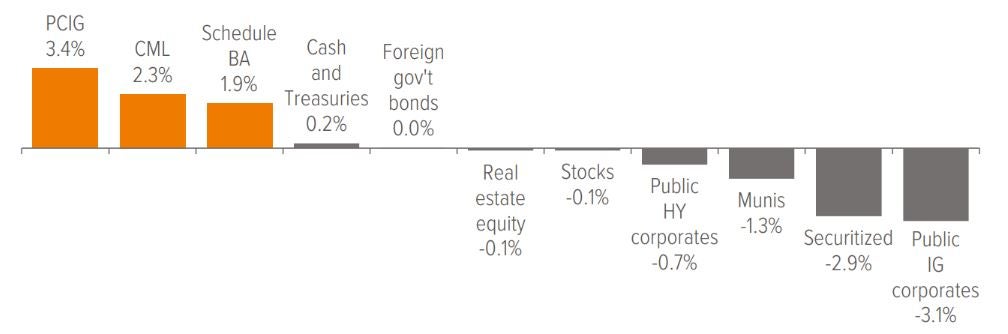

It also helps us make neat charts like Exhibit 5, which shows that big life insurers have been moving out of public market investment grade assets in search of the premium they can get in the private markets.

As of 09/12/24. Source: CapIQ, statutory filings, Voya IM. Note that the fall in securitized is almost entirely attributable to decreased allocations to agency mortgage-backed securities in favor of private commercial mortgage loans.

The risky side of it, look: We mention above that PCIG has had the same credit loss risk as better-rated public IG corporates. It’s also shown greater resilience in times of economic downturn (Exhibit 6). Unlike banks, PCIG didn’t get walloped with a lot more scrutiny after the global financial crisis, because these loans didn’t go belly-up. That’s the covenants.

But sometimes the perception of risk comes down to people not understanding why borrowers turn to PCIG rather than banks or the public market.

As of 09/30/24. Source: Cliffwater, S&P, Society of Actuaries.

Why borrowers like PCIG

I’m going to finish up with a quick look at PCIG from a borrower’s perspective. Why would you choose a form of debt that’s more restrictive and more expensive than either the public markets or the syndicated bank loan market?

There are three main reasons:

1. Creativity

Private credit delivers money to the client in a highly flexible manner, which adds more value than just a source and cost of capital. This flexibility is probably the number one reason why high-quality borrowers choose PCIG over bonds or bank loans.

The public market likes to issue 5-, 10- or 30-year investment grade bonds and 5- or 10-year below investment grade bonds. The syndicated bank market’s a little more flexible, but it’s still not big on bespoke solutions.

A PCIG lender will say, “You have holes in your amortization schedule. In other words, you don’t have any other repayments in years 3, 8 and 12. So we’re going to structure a deal for you where it’s interest only, but you pay a third of the loan back in years 3, 8 and 12.” We create an amortizing bond with three bullet payments, because that’s the structure most appealing to the CFO.

Or the CFO has a bond maturing in six months, and she wants to refinance it at today’s interest rate because she thinks rates are going higher. We’ll do that, but we’ll use the derivatives test to price the value of that option and add it onto the coupon. Or she wants a delayed draw, which is a really common request.

PCIG is also willing to do the complex analytical and legal work to structure senior secured or asset-based financing around a specific bucket of assets to help the borrower. We do this with a lot of sale and leasebacks for public companies, where the credit is still really based on the company that sold it, but they want to move some of their leverage off the balance sheet. (It also tends to give the company a little EPS tax arbitrage.)

We do a ton of business where we’re working alongside a public company to optimize its balance sheet, which makes all the scaremongering about how private markets are somehow keeping companies from wanting to go public sound a bit silly. U.S. stock market capitalization vs. GDP is more than double what it was in 1996.6 The public markets are fine.

2. Confidentiality

When you offer a public bond, you have to make your P&L and balance sheet publicly available on an ongoing basis. What if you’re a giant international consumer goods company that’s been privately held for 100 years? Or a company that’s planning to IPO, but not for another year or two? Or you’re a private equity buyout or collection of assets that has just been part of a sale and leaseback, and nobody’s ever heard of you (even though 80% of your long-term contracted revenues are from an A rated public corporation)?

This doesn’t mean PCIG lenders don’t see the quarterly financials—we absolutely do. But the borrower isn’t forced to make them public, and that’s important to a lot of companies for a lot of reasons.

3. Reliability

Private credit markets tend to stay open (with appropriate covenants) in times of stress, when the public markets close up. You don’t need to be a financial whiz to understand that it’s valuable to CFOs, treasurers and sponsors to be able to access money during bad times. These borrowers repay the favor by keeping us in their lending books through the good times as well.

How Voya can help

Voya has been a leader in the private credit market for over two decades, and for the last two years in a row, we’ve been the leading private credit manager as measured by third-party assets under management.7 We have extensive experience working with clients who are new to the PCIG space, as well as investors with an existing portfolio who are seeking a more personalized experience along with better deal flow and allocations.

This is an exciting market, and a solid one, and I believe it’s going to continue to get better—and more accessible. Let’s talk about what it can do for you.

A note about risk

The principal risks are generally those attributable to bond investing. Holdings are subject to market, issuer, credit, prepayment, extension and other risks, and their values may fluctuate. Market risk is the risk that securities may decline in value due to factors affecting the securities markets or particular industries. Issuer risk is the risk that the value of a security may decline for reasons specific to the issuer, such as changes in its financial condition.