Our panel of property pros and macro mavens discuss who’s hurting, who’s investing, and where to put money to work now.

Eric Stein, CFA

| Ever since the world locked down in 2020, commercial real estate’s half-empty offices and delinquent loans have been a recurring source of investor anxiety. But now the story is taking a new turn: financial conditions are easing, there’s a sense that office values are hitting bottom, and clients are increasingly asking us where to take intelligent risks. So, when it came time to pick a topic for our inaugural CIO Roundtable, the choice was clear. Today’s panel features investment leaders from across Voya’s equity, fixed income, private credit and multi-asset platforms. You’ll find a fair degree of alignment on many of the underlying issues. But how those issues manifest in each asset class— and what they mean for different types of investors—is where it gets interesting. Going forward, our quarterly series of roundtables will continue to bring you a diverse range of unfettered, cross-disciplinary investment perspectives. We hope this will spur further dialogue about the important issues impacting capital allocation decisions. As always, please don’t hesitate to reach out. |

Macro views: The long march to disinflation

Eric Stein: A quick glance at this call shows people dialing in both from the office and from other places. Years after the pandemic, hybrid workplaces seem to be the new normal, even for strongly office-based businesses like our own. But before we dive into what’s happening in the office market and other real estate sectors, let’s start with the big picture. As we get further into the year, rate cuts seem less and less likely in the near term. Barbara, what’s your take on where we’re headed?

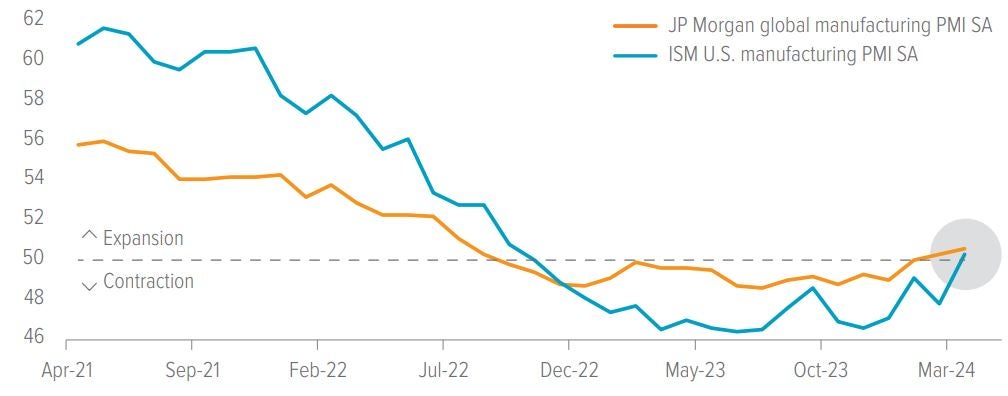

Barbara Reinhard, CFA (CIO, Multi-Asset Strategies & Solutions): I would point to two key things right now. First, a broad-based rebound in global manufacturing is starting to emerge. It’s not a full-fledged recovery yet, but the pickup in purchasing managers’ index (PMI) data is a good sign for the rest of the world, which hasn’t been in great shape. It’s also a good sign for real estate demand.

Second, I think a year from now, U.S. inflation will be much lower. I can’t say what will happen from month to month, but we’re probably headed toward the Federal Reserve’s target of around 2%. Getting there will require growth to downshift and the labor market to loosen further. That doesn’t mean the economy needs to weaken significantly, but rates may stay higher for longer than some expect. The number of cuts is less important than the rationale and the economic data, which ultimately dictate policy.

Stein: I’m in the same camp as you on inflation coming down. I’ve been more dovish on rates, although that view has been tested with every strong data point and recent hawkish Fed-speak. I think it’s less a question about where rates are going—it might just take longer to get there. Most Fed economists are Keynesian in their philosophy, and even though they won’t say it out loud, they want to promote full employment and keep the economy moving. But the data needs to let the Fed cut.

Vincent Costa, CFA (CIO, Equities): That’s the challenge—for the data to get where the Fed needs it to be. We still see commodity prices higher this year, and the risk that inflation reaccelerates, forcing the Fed to reverse course on rates, is a scary proposition. They have a window to cut, but it’s really tight.

As of 03/31/24. Source: Bloomberg, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Voya IM.

Stein: People obsess over the fed funds rate, but it’s really through financial conditions that monetary policy operates. After the massive tightening in 2022, conditions eased significantly in 2023 and into the first quarter. Everything in fixed income (other than securitized credit) is at tight spreads. Equity markets are up. The easier conditions get, the more buoyant asset markets become, then add in strong growth and sticky inflation—my view on where the Fed wants to go ends up getting pushed back.

Barbara Reinhard, CFA | Macro takeaways

|

Reinhard: I’m not too worried that we’re in for a major equity market correction. The U.S. is up nearly 30% from October lows through the first quarter, making new highs more than 20 times so far this year. Europe is at 20-year highs. Sentiment is overbought, and a lot of good news is priced in. But remember that stocks had been essentially flat for three years before the last year’s rally. It was a good launching point to get the engines revving. Earnings growth is still decent, and performance has started to broaden among cap sizes. With the buoyant economy, rising corporate profits and pivoting monetary policy, we think cyclical stocks look poised to benefit from a prolonged mid-cycle expansion.

Real estate fundamentals: Beyond the headlines

Stein: Dave and Greg, from my perspective (as more of a macro guy than a real estate expert), it seems there are fewer front-page headlines about commercial real estate than there were a year ago. Either that means the worst of market sentiment is behind us or things are bottoming out. How are you thinking about the market right now?

Dave Goodson (Head of Securitized Credit): I can understand that impression, and maybe there was more talk about it six or twelve months ago, but the reckoning is happening now. The drama around New York Community Bank (NYCB) was more of an isolated case stemming from New York’s rent control situation. But we’ve seen financial institutions in Germany, Switzerland and Canada taking hits on their real estate values. I think certain players, who perhaps weren’t as closely regulated or otherwise marked to market, were holding onto those valuations—and reality finally caught up with them. Conversely, commercial mortgage-backed securities (CMBS) bottomed back in October when rates were at their highs, and the feeling in the market has been much better since then.

Greg Michaud (Head of Real Estate Finance): On the private side, first of all, retail and industrial are doing quite well. And now office values look like they’re finally starting to trough. We only own a few office buildings in our portfolios, but some of those are actually seeing leasing momentum, and one is even close to selling. But this isn’t going to be a quick bounce back like what we saw with retail during Covid. This reckoning in offices is going to be a long, long process.

The thing that hasn’t gotten as much coverage is that apartments are starting to go sideways. Firms that made bad apartment loans are now dealing with significant foreclosures. Most of the issues are in Class A stabilized properties, where landlords are offering free rent due to overbuilding. Eventually that excess supply burns off and you’re fine, but until then, two months free rent is having a major impact on valuations. And then the next shoe to drop is likely to be hotels. When I get loan sales packages, which is basically our secondary market, I often see offices, followed by multi-family, and now a lot of hotels are coming in.

Goodson: Those issues you’re describing in Class A multi-family aren’t translating into stress in CMBS markets. Spreads year to date have been flat. Some might expect spreads to be tighter, but that usually comes in the form of agency-backed issues. Delinquencies can impact your valuations, even if the loans are credit guaranteed, because of the prepayment effect.

Dave Goodson

| CMBS takeaways

|

Michaud: On the subject of credit guarantees, the worry among mortgage bankers about Freddie and Fannie loans is that several years ago, a lot of buyers took out loans with 1-to-3-year interest-only periods as a way to improve deal cash flows that were already tight. Since then, expenses have exploded—especially insurance. In many popular multi-family markets, there’s been a 2-4x increase in insurance premiums.

As these interest-only periods end and amortization starts kicking in, borrowers now have a higher monthly payment along with those much higher expenses. That’s raising concerns that debt service coverage ratios (DSCRs) could tighten even further, below 1.25x.

Goodson: Those pressures are showing up in the CRE CLO market. At a time when credit curves are flattening across fixed income, BBB rated CRE CLOs down the subordinate stack are 50 basis points wider year to date (April 8th), which we think is appropriate. But that stress hasn’t materialized in the stabilized part of the multi-family CMBS market.

Michaud: The ray of hope for multi-family is that it’s not like the bottomless pit of office, where we estimate values have dropped 70%. Things could get ugly for multi-family in the near term, but we think it will see a natural bottom and rents should start to accelerate next year.

Impact on banks: A skittish market

Stein: Dave mentioned NYCB. It seems the banking panic from a year ago came and went pretty quickly. Anil, what are you seeing from a bank credit perspective?

Anil Katarya, CFA (Head of Investment Grade Credit): Most of the big banks have very little office exposure, and the provisioning for expected losses has been pretty strong. So it’s not really affecting spreads there.

Among the regional banks, spreads are still wider than where they were pre-Silicon Valley Bank, but they’ve come down a lot over the past year. As for multi-family, I think there’s some protection there because mortgage rates are so high—it’s difficult for renters to move out and buy a new home. So I’d say the risk for regional banks is mostly contained to offices.

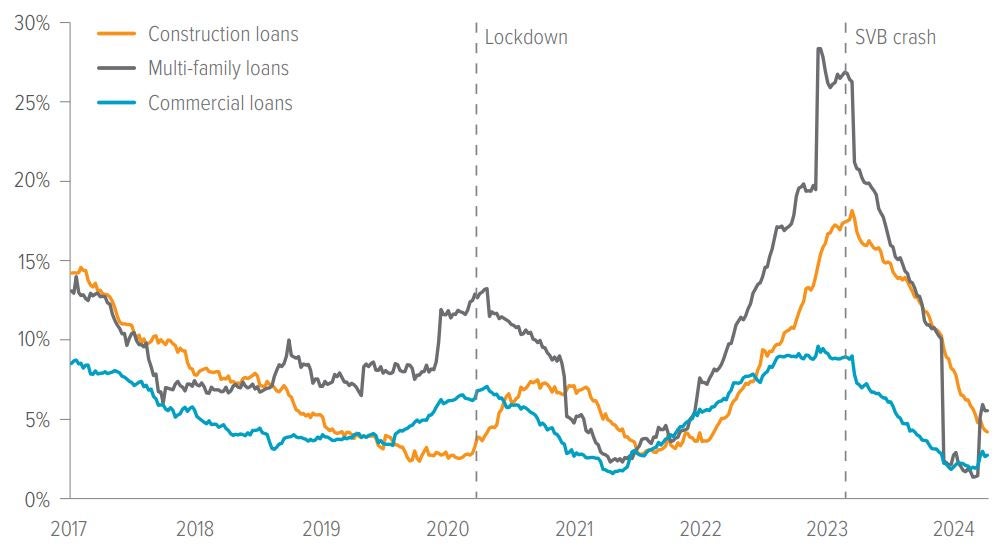

Michaud: We deal with a lot of banks in our open-ended debt fund. We just bought a large portfolio of multi-family loans—over a couple hundred million dollars’ worth— from a bank that had to sell because it was having problems with high capital charges on apartments that weren’t performing. They gave us favorable finance terms and agreed not to margin call us. So, some banks are feeling pressure to unload these apartments.

Stein: Vinnie, from the equity side, how is your team thinking about this exposure in banks and other real-estate-sensitive parts of the market?

Costa: Offices have been a challenge for a lot of the banks—more delinquencies, more non-accruals, more loan modifications. NYCB was a wake-up call for bank investors, even though it was a special case, because it showed that a meaningful increase in charge-offs can put a hole in your capital ratio. Then you have to raise capital at a distressed level and dilute your shareholders. But this isn’t anything near what banks experienced during the global financial crisis. Well, except for offices, where many banks are reserving for 800-900 bp of cumulative losses (near GFC levels), albeit on a very small slice of their overall loan books.

Stein: How much of the concern around CRE do you think is priced into bank valuations?

Costa: It’s there in spots, but in general, valuations aren’t reflecting anything more than a modest step-up in charge-offs. We’ve seen that it doesn’t take a lot to hurt capital ratios and make investors skittish. So we believe the risk doesn’t appear to be adequately priced in at the moment.

Greg Michaud

| Commercial mortgage lending takeaways

|

Capital availability: Private credit steps in

Stein: A related issue is the access to capital for real estate deals. We’ve shifted from a bank-led economy to a public credit-led economy, and now private credit is raising more money than it knows what to do with, depending on which pocket of the market you’re in. How is this affecting market dynamics?

Katarya: On the investment grade side, CRE office represents only about 1-2% of banks’ total loan books. Underwriting standards have tightened drastically. And most of these banks are just saying no to office loans. That’s probably going to continue for a while.

Costa: Yes, the banks we talk to have zero appetite for offices, even though there might be some great loans to be made at this point in the cycle, at these coupons. They simply can’t tell shareholders they’re growing an office loan book, because there’s too much uncertainty around charge-offs and delinquencies. And with Basel III now in effect, many banks are going to be spending the next several years building capital, which will limit their capacity to lend.

As of 04/10/24. Source: Federal Reserve.

Michaud: I have this gut feeling—maybe it’s the conspiracy theorist in me—that some regulators at the Fed don’t want banks having the lion’s share of the commercial real estate market anymore. But I love it that the banks are pulling back, because private lenders like us are able to pick up some very attractive deals. We’re doing construction loans at 400-500 bp over SOFR and a 60% loan-to-cost ratio. We’re doing participating mortgages. It’s been great for our space.

Goodson: Not having the banks as present in an investing capacity in securitized markets keeps our spreads wider. It also means there aren’t as many, shall we say, “less efficient” buyers in the market ready to scoop up supply when issuance gets heavy. However, one place we’re seeing a ton of demand for securitized credit is insurance companies. It used to be that insurance money was only interested in fixed-rate issuance. Now they’re going into floating-rate securities and spreading out across property types. They just have so much capital they need to put to work, and securitized credit has been a good place to do that.

Vincent Costa, CFA

| Equity takeaways

|

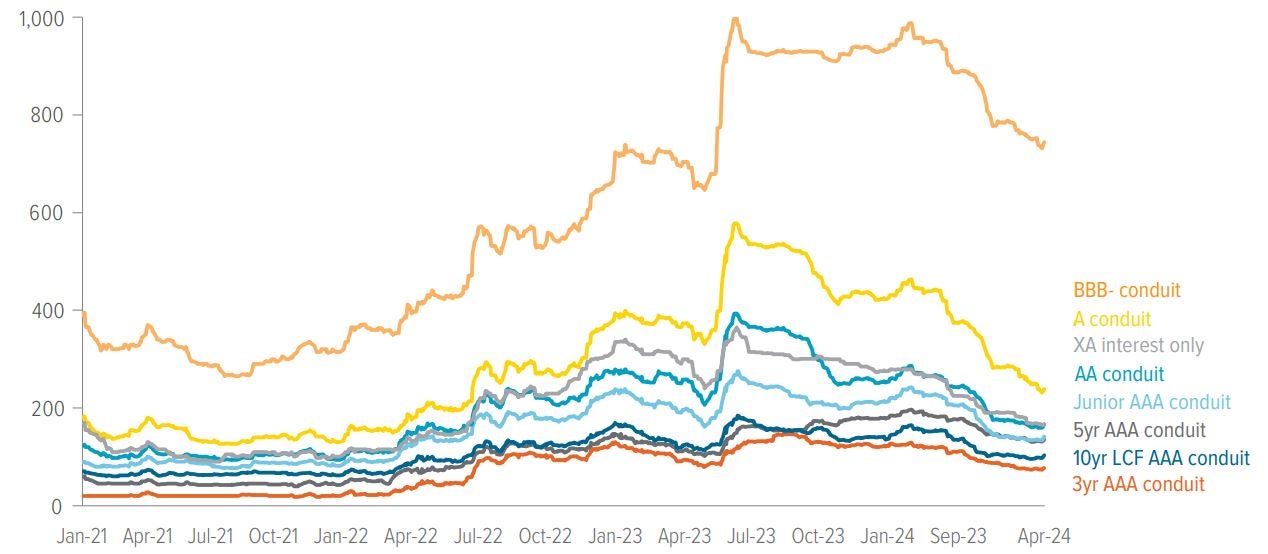

Opportunities: CMBS, CRE CLO equity, and public REITs

Stein: For investors looking to take smart risks and earn some spread premium, what are some good ways to play it, relative to what’s currently priced into markets?

Goodson: We can be pretty actionable in CMBS. Easier financial conditions are allowing supply to come through, yet there’s still a fair amount of spread premium in IG-rated classes, especially in battleground areas of the market where there’s more potential for ratings volatility. We’re talking spreads a couple hundred basis points above historical norms— irrespective of whether you’re in the single-asset single-borrower space or in conduit—due to inefficiency that needs to be priced out as a result of the problems in office. For investors who think we’re in the early part of the cycle, where CRE values start to trough and begin to repair on a medium or long duration asset, there can be a fair amount of total returns available from spread retracement.

Stein: When clients ask about where the value is in fixed income right now, the discussion often leads to securitized credit, and particularly CMBS. Money has started to come into the space, which has supported the recent rally. But there’s still value there for investors who understand the risks.

Reinhard: From an allocator’s perspective, we do like the CMBS space. The pain in that sector has been relatively orderly since the SVB shock last year. Having diversified exposure to spread product makes sense. We’re certainly not bullish on office, but if the healing process remains orderly, a total return investor should have more than enough cushion in those spreads.

Michaud: Looking at the opportunities in private finance right now, there are some pretty attractive areas for investors to pick up a 15-18% risk-adjusted yield. I’d look at buying the paper of some of the CRE CLOs that have a high percentage of loans in delinquency. I’d look at non-traded REITs with gates up, that are selling common shares or heavily discounted limited partnership interests to get liquidity in so they can drop their gates. I’d even go into a staking idea with a regional single-family developer, because they’re at a big disadvantage to the Pultes and the Lennars of the world. In multi-family, there’s potential for some strong returns on preferred equity for bridge loans, because the sellers need the liquidity. You might take some short-term pain, but the potential is there for compelling long-term gains.

As of 04/12/24. Source: Voya IM, J.P. Morgan, Wells Fargo. Conduit loan spread is to swap; interest-only spread is to Treasuries.

Stein: Greg, because of where you operate in private commercial mortgage loans, give us an idea of where spreads are today versus a year ago. 1 All spreads are Voya IM estimates.

Michaud: When the market was really hot in 2021-22, A rated deals with 60% loan-to-value were about 150 bp over the fixed-rate 10-year Treasury. Those spreads peaked last year around 200-225 bp over, and now they’re back in the 170-185 bp range. On the light transitional side, spreads last year were as wide as 350-400 bp. That’s now breaking 300-350 bp, in about 50 bp for the same type of risk.1 If there’s a quality deal out there, smaller- and medium-sized insurance companies—which generally have portfolios less concentrated in office—are chasing it.

Stein: Vinnie, what about the public REIT space?

Costa: REITs really suffered over the last two years through the Fed’s rate-hike cycle. Now that the Fed is looking to pivot, these companies are fundamentally in a good place for the most part, with low-levered balance sheets, super high-quality portfolios, and access to many sources of capital at attractive levels. You have to be selective, though, because the REIT market is so diverse. We’re focused on REITs that are well capitalized and in a position to buy assets from distressed sellers. A good example is the senior housing sector, where companies like Welltower are picking up quality properties at significant discounts, leaving a long runway for outsized earnings growth. We also like the long-term opportunity in data centers and other digital infrastructure.

Anil Katarya, CFA

| IG credit takeaways

|

Risks: Private credit corrections and the rate cut waiting game

Stein: How about the other way around? If you thought the worst was still to come, what would you do?

Reinhard: 2% real yields on 10-year Treasuries look like a pretty good hedge. But you’d have to ask, how much higher could that go? And at what point do equity markets start to worry about it? I’d be interested to know from the team—if a storm was coming, where would it originate? So much of the market operates outside of the Fed’s oversight that you could have leverage in the system that you just don’t see.

Goodson: The place where the most growth and leverage has come back into markets, that we see, is private credit, which is diverting supply from the bank loan market. As that market runs its course, it could be due for a bit of a correction, but it doesn’t look like a systemic issue.

Michaud: Institutions that hold a lot of office will probably experience some pain. Some large insurance companies have over 30% of their portfolios in office. That level is pretty common in the big guys. But even though they have a lot of exposure, they’ve spread their risk around to third-party businesses. These large insurers will get back to par eventually, but in the meantime, they’re not going to be putting as much money out into the market as they used to. The good news is that liquidity isn’t being pulled—there’s still money coming in from private pension funds, which see this market as a good entry point, as well as small and midsize insurance companies, which are going after loans down to 150 bp because they need the production. The bad news is that, with the big insurers not wanting to take on more large exposures, anything over $100 million is hard to get financing for.

Stein: How much of the issue is the base rate structure? If risk-free rates were to come down, how much would that relieve the pressure?

Goodson: Elevated rates are what’s keeping the CMBS market from rallying further. Easing financial conditions have helped spreads, but rates need to come down significantly for the rally to go much further.

Michaud: If you’re a developer or a borrower, lower rates would be a big deal, because a move in the other direction would be a real problem for them. But from a private finance perspective, I don’t think anything in the short term is going to help. When rates start coming down, I don’t anticipate a big capitulation in cap rates. It’ll take time for lower rates to get reflected in the market and provide support to property values.

Stein: Thank you, everyone. This has been a great start for our first roundtable. Looking forward to the next one.

A Note About Risk Securitized credit: The principal risks are generally those attributable to bond investing. Holdings are subject to market, issuer, credit, prepayment, extension, and other risks, and their values may fluctuate. Market risk is the risk that securities may decline in value due to factors affecting the securities markets or particular industries. Issuer risk is the risk that the value of a security may decline for reasons specific to the issuer, such as changes in its financial condition. The strategy invests in mortgage-related securities, which can be paid off early if the borrowers on the underlying mortgages pay off their mortgages sooner than scheduled. If interest rates are falling, the strategy will be forced to reinvest this money at lower yields. Conversely, if interest rates are rising, the expected principal payments will slow, thereby locking in the coupon rate at below market levels and extending the security’s life and duration while reducing its market value. Commercial mortgage lending: All investing involves risks of fluctuating prices and the uncertainties of rates of return and yield inherent in investing. Investments in commercial mortgages involve significant risks, which include certain consequences as a result of, among other factors, borrower defaults, fluctuations in interest rates, declines in real estate values, declines in local rental or occupancy rates, changing conditions in the mortgage market and other exogenous economic variables. All security transactions involve substantial risk of loss. The strategy will invest in illiquid securities and derivatives and may employ a variety of investment techniques, such as using leverage and concentrating primarily in commercial mortgage sectors, each of which involves special investment and risk considerations. |